Neurofeedback for Attention Deficit and Executive Functioning – Part 1

- joshuamorrow244

- Apr 25, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Apr 28, 2025

There are many people in the current day and age that find it increasingly difficult to focus, control their attention, and to really get after completing the tasks that they want to get to, or maybe even just the things they know they should do. Maybe it is ADHD, maybe it is a lack of willpower or motivation, maybe it is the anxiety or depression or sleep difficulties or poor diet or the lack of exercise or the psychological trauma. Maybe it is a combination of any number of things, but any way it goes, many people struggling with loss of attention control and executive functioning deep down want to change.

Generally people with these struggles want to be better, to be freed from these struggles, some to stop negative feelings that chronically live inside of them, and others simply want to be more able-minded to get more of what they desire. This is human nature, and also what this article is about, to share about one way that this can be done, a way that I have personally see be quite helpful for my clients, and a way in which is unknown to most people – Neurofeedback – and how it can help you or a loved one regain the natural capability for sustained focus, attention, and executive functioning that is a naturally given birthright that every individual is capable of and deserves.

So many people struggling with attention issues and executive function deficits are left at a loss of what to do about it, I know this because I work everyday with people in my practice as a therapist who see me for this very reason. One very challenging piece for many people is that every time they have tried to change, it doesn’t seem to stick. They read this book, they start a new diet, they begin doing some new fitness routine, they pick up this activity they have always wanted to do, and it lasts maybe a few days, maybe a few weeks, but usually not more than a month or two. It never seems to stick, and slowly all the old patterns return.

The scattered mind, jumping from task to task, easily going with the constant pull of distractions, the de-motivation states and that feeling of knowing what you have to do and really wanting to want to do that thing, but feeling paralyzed and unable to move your body to do that thing. All you have to do is move your body, but for some reason it just won’t happen. Unable to manage your time and being flooded with overwhelming anxiety when all of a sudden there is so much to do. The feelings of lowered self esteem from repeated failures to control these repeating patterns, loved one’s reactions to these patterns you have...their disappointment and silent judgment... that burdensome weight of the feeling that there is something wrong with you, looking out at others and wondering why you can’t “have your shit together” like all the other people. And to top it all off, we then blame ourselves. We think we can’t do it, and chronic feelings of weakness or shame live constantly in the background of our life, arising every time we fail in our attempts to change or every time one of these uncontrolled patterns again cause us distress in our work, our relationships, or our own standards for our-self.

Having difficulties with attention and executive functioning is not small thing, as it often leads to compounding emotional, relational, and financial difficulties that sadly tend to exacerbate the attention and executive functioning problems that have led to these other difficulties. This is what we call a positive feedback loop, the cognitive difficulties make the emotional difficulties worse, which makes the cognitive difficulties worse, which make the emotional difficulties worse, and on and on and on...it is a very negative positive feedback loop for the person experiencing it. This is a serious problem, as the mental faculties lost are central to creating a positive life experience for ourselves and those around us. If we don’t have conscious control over our ability to generate focus or direct our attention and behavior, we are going to have many challenges arise in life that we are not equipped to deal with. People struggling with this often learn to find some sort of equilibrium and cope with these problems, wanting and wishing to get better, to not have to deal with them, but having a learned hopelessness about actually being able to change it... with this constant nagging negative feeling about themselves lurking in the shadows of their inner world.

But I am here today with you to share that if you are suffering from these difficulties, it is not your fault, and I will tell you why. Two words: Brain Dysregulation. When we talk about attention challenges and executive functioning difficulties, we're really talking about differences in how certain parts of your brain function and communicate with each other. Research has consistently shown that these issues aren't simply a matter of willpower or character—they are a reflection of real differences in how the brain is working.

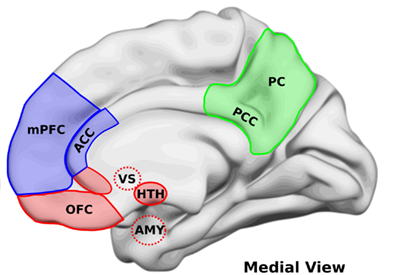

Let’s start by looking at the more severe and commonly known form of attention control problems and executive dysfunction– Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. The ADHD brain shows distinct patterns in several important regions:

The Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) acts as your brain's "CEO," responsible for planning, decision-making, and controlling impulses. In individuals with ADHD, this region often shows reduced activity and size compared to neurotypical brains (Arnsten & Rubia, 2012). This explains why starting tasks, staying organized, and resisting distractions can be so difficult with ADHD—your brain's executive is working with limited resources.

The Parietal Lobe (PC), particularly the inferior parietal regions, helps you maintain focus on relevant information while filtering out distractions. Research using advanced brain imaging has shown that these areas function differently in people with ADHD, making it harder to ignore irrelevant stimuli in your environment (Cortese et al., 2012).

The Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC) helps monitor your actions and detect errors. When this region isn't functioning optimally, as often seen in ADHD, it becomes more difficult to recognize when you've gotten off track or made a mistake, contributing to the feeling of "where was I going with this?" that many people with ADHD experience regularly (Bush et al., 2005).

Even more important than individual brain regions are the networks that connect them. Modern neuroscience has revealed that ADHD often stems from problems with how these networks communicate:

The Default Mode Network (DMN) is active when your mind is wandering or daydreaming, often called the “idling state”. It is a common experience when driving in a car or doing simple household tasks. In neurotypical brains, this network quiets down when concentration is required. However, research has shown that in individuals with ADHD, the DMN often remains inappropriately active during tasks requiring focus, contributing to distractibility and wandering thoughts (Castellanos et al., 2008).

The Central Executive Network (CEN) activates when you need to pay attention to something specific. In people without ADHD, this network and the DMN work in a complementary balance—when one is active, the other quiets down. For those with ADHD, these networks often fail to coordinate properly where the DMN continues to be active even after the CEN engages, leading to the frustrating experience of trying to focus while your mind continues to wander (Fox et al., 2005).

The Fronto-Parietal Network helps you adjust your attention from moment to moment based on changing demands. In ADHD, connections within this network are typically weaker, making it more difficult to shift attention appropriately or maintain focus on non-engaging tasks (Cortese et al., 2013).

Understanding that ADHD stems from brain dysregulation rather than personal failing is incredibly important, and my hope that it also removes some of the shame and stigma that exist around these challenges for others. These neurobiological differences create very real barriers to consistent focus and self-regulation that can't simply be overcome through greater effort or willpower alone.

Imagine trying to drive a car with an engine that misfires intermittently, or maybe more than intermittently…. no matter how skilled a driver you are, that underlying mechanical issue will make your journey much more difficult, maybe even impossible depending on the journey you are trying to take. Similarly, when your brain's attention networks aren't communicating effectively, even simple tasks can require extraordinary mental effort, or perhaps if bad enough can’t happen at all.

The good news is that the brain has a remarkable capacity for neuroplasticity—the ability for the brain to change and adapt its wiring and firing throughout life. Just as physical therapy can help rehabilitate an injured limb, neurofeedback offers a way to retrain these dysregulated brain regions and networks, leveraging neuroplasticity and helping them function more effectively and efficiently. It’s like popping open the hood of the car and doing some maintenance and tuning work, it takes a little bit of time and some elbow grease, but if done right the engine will purr.

In the next part, we will explore how neurofeedback works to address these neurobiological differences in ADHD, offering a path forward that doesn't rely solely on medication, sheer force of will, or resigned hopelessness.

References

Arnsten, A. F., & Rubia, K. (2012). Neurobiological circuits regulating attention, cognitive control, motivation, and emotion: Disruptions in neurodevelopmental psychiatric disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(4), 356-367.

Bush, G., Valera, E. M., & Seidman, L. J. (2005). Functional neuroimaging of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A review and suggested future directions. Biological Psychiatry, 57(11), 1273-1284.

Castellanos, F. X., Margulies, D. S., Kelly, C., Uddin, L. Q., Ghaffari, M., Kirsch, A., Shaw, D., Shehzad, Z., Di Martino, A., Biswal, B., Sonuga-Barke, E. J., Rotrosen, J., Adler, L. A., & Milham, M. P. (2008). Cingulate-precuneus interactions: A new locus of dysfunction in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 63(3), 332-337.

Cortese, S., Kelly, C., Chabernaud, C., Proal, E., Di Martino, A., Milham, M. P., & Castellanos, F. X. (2012). Toward systems neuroscience of ADHD: A meta-analysis of 55 fMRI studies. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(10), 1038-1055.

Cortese, S., Imperati, D., Zhou, J., Proal, E., Klein, R. G., Mannuzza, S., Ramos-Olazagasti, M. A., Milham, M. P., Kelly, C., & Castellanos, F. X. (2013). White matter alterations at 33-year follow-up in adults with childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 74(8), 591-598.

Fox, M. D., Snyder, A. Z., Vincent, J. L., Corbetta, M., Van Essen, D. C., & Raichle, M. E. (2005). The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102(27), 9673-9678.

Comments